A BRIEF HISTORY OF CHINA

China is one of the world’s oldest civilizations, with thousands of years of continuous history. The first concrete evidence of civilization, dating back to the Neolithic era, was discovered in various regional centers along the Yangtze River and Yellow River valleys, although the Yellow River is said to be the cradle of Chinese civilization.

In between eras of multiple kingdoms and warlords, Chinese dynasties, or more recently republics, have ruled a China of varying shapes and sizes. This began with the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC, when Qinshihuang united the various warring kingdoms, thus creating the first Chinese empire and beginning construction of the Great Wall. The Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD) was the first to embrace the philosophy of Confucianism, the tenets of which are still pervasive throughout modern Chinese society. Emperor Wu, the seventh of the Han emperors, extended the Chinese empire by pushing the invading Huns back into what is now Inner Mongolia. This enabled the first opening of trade connections between China and the West along the Silk Road.

Successive Chinese dynasties used their sophisticated bureaucratic systems to control vast territories. In alternating periods of disunity, China was occasionally dominated by inner Asian peoples, most of whom were eventually assimilated into the Han Chinese population. Political and cultural influences from many parts of Asia, brought by waves of immigration, periods of expansion and cultural assimilation, formed the modern culture of China.

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), founded by the Manchus, was the last dynasty and only the second not dominated by ethnic Hans, although the Manchus adopted the Confucian norms of traditional Chinese government. By the 19th century, the Qing empire had economically stagnated and was threatened by Western imperial powers. The Qing were soundly defeated in the First Opium War (1842) by the British, resulting in the ceding of Hong Kong and the legalization of opium imports. By 1870, opium accounted for over 40 percent of all goods imported to China. Subsequent civil wars and military defeats to outsiders continually weakened the government until it was overthrown by several factions united under the revolutionary ideas of Sun Yat-sen.

After Sun’s death in 1925, Chiang Kai-shek seized control of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party or KMT) and brought most of China under his control, eventually turning on the Communist Party, driving them across China's most desolate terrain to Yan'an on the Long March. From there, the Communist Party regrouped under the leadership of a young Mao Zedong, returned north and succeeded in toppling the KMT and forcing them to the island of Taiwan in 1949.

Chairman Mao’s original social and economic plan, the Great Leap Forward, was a complete disaster. It resulted in an estimated 45 million deaths, mostly from starvation. In 1966, Mao and his allies launched the Cultural Revolution, which sought to eradicate all traditional and capitalist elements from Chinese society.

After Mao’s death in 1976, reformers led by Deng Xiaoping gained prominence and most of the Maoist Reforms’ associated with the Cultural Revolution had been abandoned by 1978. The economy proceeded to blossom under open market reforms and the welcoming of foreign investment allowing China to boast double-digit economic growth every year. China formally joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Today's China continues to grow economically and transform culturally, although this growth and change is disproportionately beneficial to some, a fact evident in large modern cities such as Shanghai.

The Bund, 1920s

Suzhou Creek, 1920s

Nanjing Road, 1920s

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SHANGHAI

Shanghai’s historical evolution from a sleepy fishing and textile port on the Yangtze Delta to a fully fledged world-class city has been formed by lucrative Chinese-Western trading relationships, cheap and plentiful labor from impoverished rural areas and the city's relative peace compared with the rest of China in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Shanghai emerged as a popular export center for the British East India Company in the 18th century as Chinese silk, porcelain and tea became popular in Great Britain. However, the isolationist Qing Dynasty had no desire for Western goods, thus creating an unacceptable trade imbalance. To rectify the situation, the British took advantage of the Chinese penchant for opium smoking by cultivating and importing a superior product from India. When China resisted by seizing the opium and restricting trade access, the industrialized British army overpowered the Chinese in what became known as the First Opium War. In the resulting 1842 Treaty of Nanking, the Chinese ceded Hong Kong and extraterritorial concessions in five cities, including Shanghai.

The British named their new autonomous settlement along the Huangpu River the Bund, which was later consolidated with the American community to form the International Concession. The French and Germans also carved out sovereign concessions, where they were not subject to Chinese law and could trade freely. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, while most of China was suffering from internal conflict and poverty, Shanghai blossomed as foreign residents built up an impressive infrastructure. While the rest of China was entrenched in civil strife, Shanghai developed some of China’s best roads and hotels, its first gaslights, electric power, telephones and trams. The city continued to prosper throughout the first decades of the 20th century, welcoming Japanese, Russians and other Europeans, each bringing their own customs and culture. By the 1920s and 30s, Shanghai had grown into the wealthiest and most cosmopolitan city in all of Asia. It wasn’t just British financiers and Japanese industrialists that were getting rich; gangsters and thugs from all nationalities were able to establish a foothold. The city became legendary for debauchery. At one time the International Settlement alone boasted nearly 700 brothels, earning Shanghai the dubious titles of *City of Sin' and the 'Whore of the Orient’.

The Japanese invaded the International Settlement in 1942 and interned Allied nationals in detention centers until the Japanese surrendered to the Americans in 1945. Soon after, the Communists liberated Shanghai in 1949, and ensured that the party was over. The city immediately became considerably grayer. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Shanghai was the headquarters of the Gang of Four, who purged the city of the ’Four Olds': old habits, old culture, old customs and old ways of thinking. By the time they were finished, the only evidence of Shanghai’s earlier prosperity and decadence was the crumbling infrastructure left behind. When Richard. Nixon visited Shanghai for his historic meeting with Premier Zhou Enlai in 1972, the city was completely dark after nightfall. Even in 1988, ten years after Deng Xiaoping launched the economic reform era, the tallest building in the city was the Park Hotel, built in 1934.

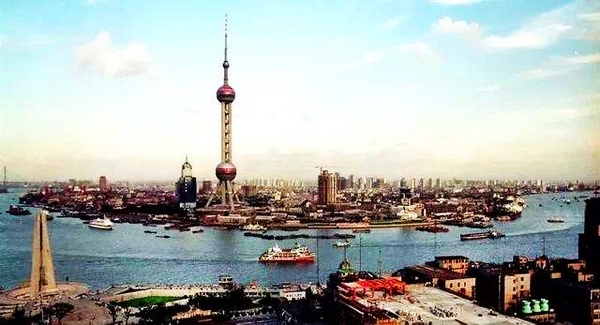

In 1990, however, the government in Beijing decreed that Shanghai was to be the epicenter of China’s ambitions of becoming a global economic powerhouse, allocating national revenues to store up neglected infrastructure and subsidize business development. Pudong, consisting at the time of a few settlements and rice paddies, was declared a Special Economic Zone. The city quickly changed beyond recognition as it rushed to make up for the 40 years it had lost during Communism. Tens of thousands of foreign and Chinese investors poured money into new enterprises and infrastructure, while hundreds of thousands of Chinese laborers migrated from their homes across the country to Shanghai to build it.

By the time Shanghai was awarded the 2010 World Expo in 2002, it was a modern megalopolis with a population approaching 20 million. The city spared no expense to impress visitors to the 2010 Expo, inspiring a building frenzy that included a new terminal in Pudong International Airport, upgrades to the Nanjing Lu Pedestrian Mall and the Yan’an Elevated Expressway, new bridges and an underground public transportation system that has now overtaken London's in size. Shanghai has truly regained what many feel is its rightful place on the world stage.

For a visitor from the recent past, Shanghai would be virtually unrecognizable. Basking in its boomtown exuberance, 21st-century Shanghai emanates a feeling of energy and adventure. This is a city which has no time for nostalgia as it blasts off into the future, never slowing and certainly not stopping for a moment to smell the roses. Then again, making money through economic adventure and old-fashioned industriousness is nothing new to the Shanghainese. The original characteristics that created Shanghai prosperity are still prevalent today: Chinese-Western trading relationships, innovative and entrepreneurial Chinese and Asian migrants, cheap, hard-working and plentiful labor and relatively hands-off government policy.

Behind Shanghai's modern glitz, there are plenty of relics of the past. The architecture and street ambience of the Bund and the French Concession offer visitors a glimpse of Shanghai’s colorful past, and any visitor who compares the elegant villas of the French Concession to the crowded quarters of the Old City can quickly imagine the historic income disparities of 1920s Shanghai.

While at times spectacular, Shanghai’s incredibly rapid rise can make it feel like the latest thing, a city about the here and now rather than a place with its own character; and at times it just feels like a giant construction site. Either way, Shanghai is sure to dazzle and intrigue any visitor, and it's worth taking a moment to reflect on where it came from, and where it might be going - since it's evolving daily and what remains of its past is fast disappearing amidst a sea of change.

Shanghai Skyline 2018

Pudong Skyline 1994

THEN AND NOW

The upper photo is the iconic skyline of the Lujiazui financial district of Shanghai, boasting the world’s third tallest building (with the second tallest coming soon) and a GDP to rival that of many nations. Below it is an image of the same area prior to development when it was a mixture of rice paddies and small settlements.

While the area is impressive in its own right, what's even more jaw-dropping is that all that development took place In less than 20 years. The before image was taken in 1990. Add the fact that comparable scenes exist all over China (the country has more than 100 cities of more than one million people) and one begins to develop a sense of what the Chinese miracle really means.

Source from: Expat Essientials